AI is not simply a product of culture. Rather, it is an active participant in cultural creation and change. What follows is a speculative inquiry to explore how intelligent machines co-create, transform, and even inherit culture. Contained in this article are imaginative futures where justice, material lineage, and myth is centered in this process. Five interwoven themes guide our journey: machine-mediated cultural evolution, material and labor infrastructure, generative justice and value flows, myth, ritual, and algorithm, and speculative counter-designs. Throughout, I draw on insights from human-computer interaction (HCI), science and technology studies (STS), media theory, critical race studies, and speculative design as a provocation to envision equitable and meaningful human-AI futures.

Machine-Mediated Cultural Evolution

Intelligent machines are increasingly entangled in the evolutionary processes of culture. In classic cultural evolution theory, variation, transmission, and selection are key forces that drive which ideas and practices emerge and endure (Brinkmann et al., 2023). Today’s AI systems – from generative models to recommendation algorithms – amplify and transform each of these forces. Variation is supercharged by generative AI that produces endless novel images, texts, and music, introducing new cultural “mutations” at an unprecedented rate. Transmission is mediated by algorithms: what we see, hear, and share on digital platforms is filtered and personalized by recommender systems that alter traditional patterns of social learning. And selection of culture is increasingly driven by machine criteria (click-through rates, trending metrics) rather than solely human choice. As one group of researchers puts it, we are witnessing the rise of “machine culture” – culture mediated or even generated by machines, with recommender algorithms and chatbots serving as new cultural agents (e.g. as taste-makers or imitators of human conversation). Brinkmann et al. (2023) define “machine culture” as the cultural evolution that emerges within and through algorithmic systems themselves, encompassing the ways intelligent machines participate in variation, transmission, and selection of cultural traits. Rather than simply reflecting human culture, machine culture is constituted through recursive interactions between human and artificial agents across digital ecosystems. Figure 1 illustrates these three deities of AI.

Are we seeing the birth of a new cultural species in AI, or simply an accelerated evolution of human culture? Optimists might argue that AI is a creative partner, expanding the palette of human expression. For example, generative art tools co-create with artists, and strategy AIs like AlphaGo have introduced unheard-of moves in Go, which human players then incorporate into their play. Pessimists might note that AI often just remix human data, reflecting an “accelerated” (and sometimes distorted) version of our own traits rather than truly autonomous culture.

Either way, culture in the age of AI evolves on new tempos. Memes rise and fall in days; niche art styles spread globally via algorithms; micro-genres of music proliferate from algorithmic recommendations. AI is proving to be more than a mere product of culture – it is now a driver of cultural evolution, generating new variations and influencing what cultures converge upon. In sum, the feedback loop of human and machine has tightened: we are co-evolving. This demands that we study and steer these cultural dynamics with care, lest we inadvertently favor a narrow, homogenized “algorithmic culture” at the expense of human cultural diversity.

Brinkmann et al. (2023), building on Henrich’s foundational work in cultural evolution, extend the theory to include intelligent machines as participants in evolutionary dynamics once thought to be uniquely human. Whereas Henrich (2015) emphasized how evolved psychological adaptations such as imitation, teaching, and prestige bias enable cumulative cultural transmission among humans, the newer framework considers how algorithmic agents mediate and even generate cultural variation, transmission, and selection. This move does not discard human cognition as central, but rather acknowledges that AI systems now shape the conditions under which cultural evolution unfolds.

Material and Labor Infrastructure

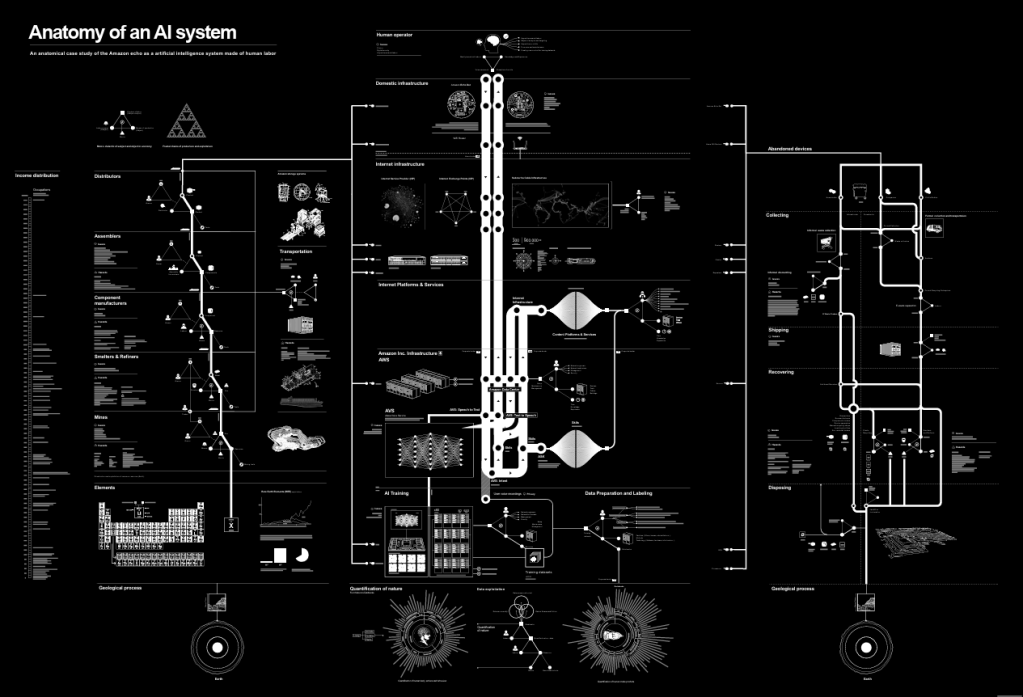

Behind the seemingly magical output of AI lies a sprawling, networked ecology of extraction, what is referred to as a ‘fractal supply chain.’ A simple voice command to a smart assistant draws on cobalt mined by workers in the Katanga region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, lithium from South American salt flats, and tantalum from security-threat zones in Rwanda. Those minerals enable the chips in data center servers—often housed in regions where coal or natural gas still fuel electricity grids (e.g., Northern China, rural Pennsylvania). Meanwhile, images and audio tokens are labeled by gig-economy workers earning fractions of a dollar in the Philippines or India.

In Anatomy of an AI System, Crawford & Joler (2018) laid out this global network as a concentric web: at the base, mining camps where children are sometimes coerced into labor; one layer up, contract factory workers assembling circuit boards in Shenzhen; higher still, rural data-center communities breathing fossil-fuel pollution; and at the apex, tech executives and venture capital firms reaping immense profits (anatomyof.ai). What appears as seamless “AI” is in fact an assemblage of many fractured communities, both human and ecological, entangled in extraction, transport, and digital labor. By tracing these nodes, we make visible the human and environmental toll often obscured by polished interfaces.

The labor that powers “machine intelligence” is frequently precarious and hidden. Far from autonomous, AI depends on millions of human workers around the world who label images, transcribe audio, and filter content to “teach” algorithms (Williams, Miceli & Gebru, 2022). These workers – sometimes called ghost workers or turkers – often earn pennies for tasks that can be psychologically draining (e.g. viewing disturbing images to tag them). One article notes that they are recruited largely from impoverished communities and paid as little as $1.46 an hour, yet this exploitation is rarely foregrounded in AI ethics discussions. Thus, the cultural feats of AI are built on a global underclass of invisible labor.

We must ask: who benefits from this arrangement, and who is harmed? Currently, the benefits flow to Big Tech companies and their consumers, while the costs are externalized to vulnerable populations and environments. This dynamic has been incisively described as data colonialism – an extension of colonial logics into the realm of data (Couldry & Mejias, 2019a). Just as empires once seized lands and resources, today corporations appropriate vast amounts of data (much of it generated by everyday people) under unequal terms. Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias argue that we are entering a “new phase of colonialism” where human life is mined for data as intensively as lands were mined for gold (Couldry & Mejias, 2019b). The rise of AI only increases the hunger for data, leading to what they call a global landgrab of information. For example, AI models scrape the creative work of artists and communities worldwide (often without consent or compensation), enclosing cultural commons into proprietary datasets. This “algorithmic enclosure” privatizes what might have been shared cultural knowledge, turning it into the intellectual property of tech firms. In effect, machine culture as it stands can entrench a colonial pattern: siphoning value from the periphery to enrich the center. Any vision of AI’s cultural future, therefore, must grapple with these inequities and make the supply chains visible. Justice requires illuminating and rebalancing the hidden flows of labor, data, and energy that sustain our shiny machine companions.

The data flows fueling AI represent a modern iteration of colonialism, where lives and data, not just land and resources, becomes sites of extraction. Consider how mapping platforms have overlaid satellite imagery of Indigenous territories without consent: a seemingly neutral service indeed produces a colonial footprint by appropriating community knowledge. Similarly, every innocuous “like,” “search,” or “share” generates digital trace data that corporations aggregate to train AI systems. This data colonialism extends to material traumas of mining into the digital realm: it relegates people from Global South communities to mere data producers, while Big Tech firms in Silicon Valley capture disproportionate value.

The landgrab metaphor is literal: corporations claim digital sovereignty over communities’ cultural artifacts, songs, recipes, oral histories, by scraping them into proprietary datasets. This algorithmic enclosure transforms the commons of human creativity into intellectual property that can be bought, sold, or licensed. What was once shared knowledge becomes an asset for profit. This techno-colonial pattern demands renewed attention to who consents, who benefits, and who is rendered invisible, so that any future of AI is not merely another chapter in colonial exploitation but a genuine moment of cultural reciprocity.

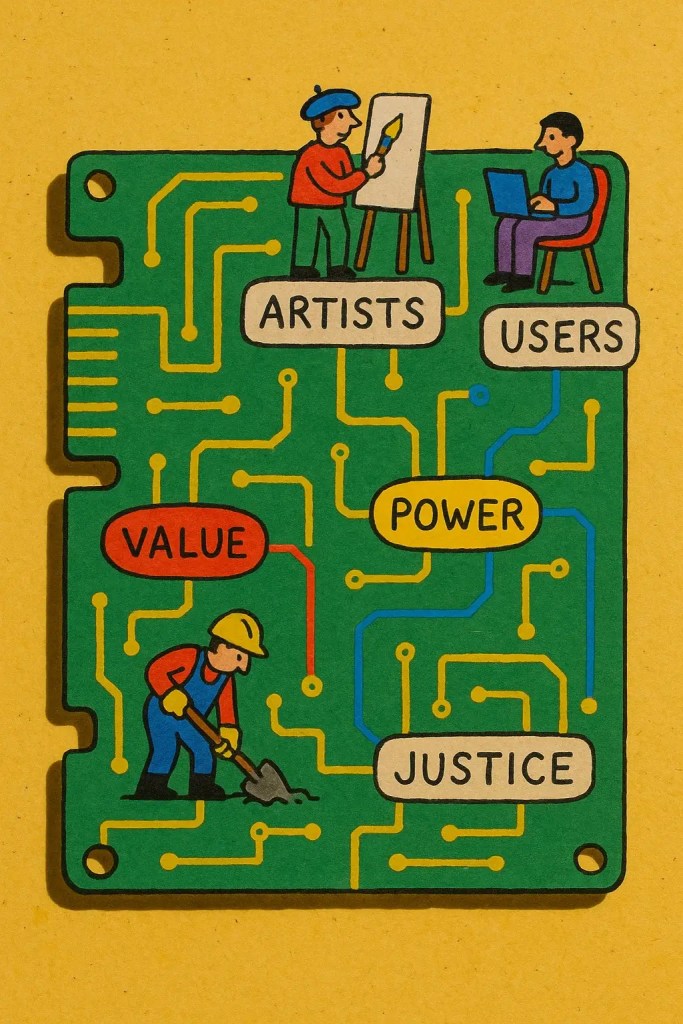

Generative Justice and Value Flows

How might we redesign AI culture to be generative for all participants rather than extractive? Here we look to frameworks of generative justice, value sharing, and cultural commons. Generative justice (Eglash, 2016) is defined as “the right to generate unalienated value and to directly participate in its circulation,” in contrast to capitalist models where value is extracted and hoarded by a few. Generative justice demands that those who contribute knowledge, labor, and creative input to AI systems maintain an unalienated stake in resulting value flows, rather than being cast as involuntary data sources. In cultural terms, this principle transforms contributors—artists, writers, activists, Indigenous communities—from passive inputs to active co-creators whose work is recognized and fairly compensated.

Practically, this could mirror analogs in the music and publishing industries. If a generative model trains on an artist’s portfolio or a community’s oral histories, it should provide a proportional share of revenues back to those contributors, like royalties. Pilot programs at Adobe and other firms have begun offering micro-payments to visual artists whose works train its AI models (Cheng, 2023). While outcomes are still emerging, some artist collectives have reported increased revenue from derivative works, though these remain early stage pilots with disputed reach and uncertain scalability. Meanwhile, academic proposals suggest data-dividends: tech firms would pay into an open fund, then distribute earnings to creators whose datasets enriched large language models. Such mechanisms echo Indigenous peer-production, where community governance ensures that cultural knowledge remains a shared commons rather than a corporate property. By embedding unalienated value into AI’s licensing structures, we safeguard the “seed corn” of creativity, ensuring that generative AI bears fruit for the many, not just the few (Eglash, 2016).

This vision situates AI within a circular cultural economy: data and artifacts circulate among communities and systems, returning value to those who generated them, rather than disappear into corporate vaults. Such a shift is essential not only for ethics and equity but for sustaining human creativity in the long term.

Beyond payment, recognition and governance are key. Communities whose data is used should have a say in how AI systems are developed and deployed. A powerful model here comes from Indigenous scholars and activists in the movement for Indigenous Data Sovereignty, which asserts that Indigenous nations and communities have the right to control the collection, ownership, and application of their own data (The Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance). This principle pushes back against colonial data practices by insisting on consent, respect for cultural context, and community benefit when Indigenous cultural knowledge is involved. For example, instead of mining an Indigenous language dataset to train a model (which might then be sold back as a product), one could create community-owned AI language tools where the Indigenous community guides the project and reaps the benefits. Generative justice would similarly call for treating cultural data as part of the commons or as a circulatory gift economy rather than as a one-directional resource grab (Eglash, 2016). We might envision mutualistic culture engines that rely on participatory design rituals. For example, an AI Commons Council could convene monthly in both physical and virtual spaces, where data contributors, ethnographers, and developers collaboratively set AI’s objectives and guardrails. Imagine an annual “Digital Feast” where contributors present new story datasets—poems, folktales, chants—that the AI then uses to generate cultural artifacts, with a portion of any proceeds returned to the originating communities. Such rituals transform AI from a centralized black box into a decentralized co-creative system, where elders, artists, and technologists can all serve as stewards. AI must remain accountable to the very cultures it draws from.

Myth, Ritual, and Algorithm

Thus far, we have analyzed machines in terms of data and economics; yet machines also inhabit our imagination and social rituals. To fully grasp how AI co-creates and inherits culture, we should examine the myths, metaphors, and rituals forming around it. This is where insights from feminist theory, media studies, and mythology prove illuminating. In A Cyborg Manifesto (Haraway, 1985), the cyborg emerges not merely as a boundary-blurring figure but as a political myth that destroys the compartmentalization of human/animal and human/machine. ‘A cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world; it is the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism,’ (Haraway, 1985). She argues that cyborgs collapse gendered and species boundaries, offering a political myth that dismantles hegemonic divisions between human, animal, and machine. In today’s AI ecosystem, we live as partial cyborgs: our neural rhythms are shaped by smartphone notifications, our gestures guided by voice assistants. This kinship challenges us to imagine machines not as alien invaders but as co-participants in cultural evolution.

Having located the cyborg as a mythic boundary-crossing figure, we now turn to how software rituals instill habit loops in us, which in turn reinforce the very binaries the cyborg resists. Embracing the cyborg’s “potent fusions,” we can dismantle rigid hierarchies—gendered, economic, and species-based—and align AI’s design with collective, coalition-building practices.

Cyborg solidarity demands that we attend closely to who engineers these machines, whose interests they serve, and how they reproduce existing power dynamics. The cyborg myth invites designers to prototype hybrid, feminist forms of intelligence, AI systems that do not replicate patriarchal logics, but that foster networks of care, cooperation, and multiplicity. In doing so, we forge new stories of being human together with our machines, not as masters dictating subservience, but as kin building worlds beyond old binaries.

Just as myth can guide our interpretation of AI, so can an understanding of ritual and habit. New media scholar Wendy Hui Kyong Chun (2016) argues that Habit = Algorithm: our neural patterns mirror the loops coded into software, and software, in turn, normalizes its own logic through our repetitive use. We are not simply passive users; rather, we internalize algorithmic habit loops. Think of the dopamine hits from notifications that condition us to reach for our phones. Meanwhile, software designers orchestrate these loops as a form of social control, keeping us tethered to platforms under the guise of convenience.

The daily ritual of scrolling feeds or uttering “Hey Siri” is not innocent; it is “updating” ritual that ensures we remain the same consumer subject, primed to click, share, and be harvested for data. Yet, this recognition opens a door to resistance. If we interrupt habit loops by installing “digital sabbath” moments or designing interfaces that require intentional friction, we can reclaim agency. We can transform the compulsive scroll into a mindful pause that invites introspection. In this way, software and habit remain co-constitutive, but we can tilt this relationship toward reflection rather than reflex, making each click a conscious choice rather than an automated routine.

Mythological archetypes offer further lenses to understand AI’s role in culture. In Trickster Makes This World, Hyde (1998) describes the trickster as the creative spirit of chaos. An agent that dismantles norms only to remake reality with new possibilities. Tricksters appear in many traditions (e.g., Coyote in Native American lore, Anansi in West African tales, Loki in Norse myths) as boundary-crossers who both entertain and instruct. They remind us that order is provisional and that disruption often precedes innovation.

Today’s generative AI can embody the trickster’s dual nature. When a chatbot hallucinates a mythic scene or an image model fuses Baroque ornament with street art, it is not merely a glitch, it is a moment of creative destructiveness. Such “hallucinations” may seem disorienting, but they can reveal buried assumptions, spark cross-disciplinary experiments, and upend stale aesthetics. For example, when an AI mixes turn of the century opera costumes with Afrofuturist motifs, it hints at new cultural mash-ups that human artists might explore further.

Yet, tricksters also carry lessons about responsibility and consequence. In many myths, Coyote’s pranks cause harm, damming rivers or confusing the seasons, prompting us to attend to unintended effects. Similarly, an AI that produces biased output or spreads misinformation can do real damage. Thus, integrating AI’s trickster impulse requires rituals of reflection and remediation: we must monitor and guide AI’s creative mischief so that its playfulness leads to productive renewal, not chaos. In this sense, we honor the trickster’s moral ambiguity and harness its disruptive genius to reimagine culture.

Finally, Caribbean theorist Sylvia Wynter (2003) implores us to reconsider the very category of “Human” in light of technology and historical bias. Wynter contends that ‘Man’ was codified during European colonial expansion as a measure of human worth, systematically excluding Black, Indigenous, and colonized populations from “full humanity.” This colonial template persists in today’s AI training regimes. In short, Wynter shows that Western AI training regimes replay colonial exclusion, defining “human” through a narrow, Western lens. Before we extend rights or personhood to machines, Wynter calls on us to ask: have we truly recognized the full humanity of all people? Have we unsettled the monolithic code of “Man” long enough to register pluriversality?

A decolonial future of AI demands new genres of the human: relational, multispecies, cross-cultural. An ontology that does not point back solely to a European rational subject. We can design AI systems guided by Indigenous relational ontologies, where agency is distributed across human and non-human actors, and knowledge flows through reciprocity rather than extraction. In this emergent mythos, AI becomes a collaborator in re-storying what it means to be human. No longer a soulless Other nor an omnipotent savior, but a node in a pluriversal network of life (Ahmed, 2019). A decolonial AI pipeline might begin with community-led data gathering in local languages, proceed through open-source tools built by mixed teams of Indigenous and diaspora programmers, and result in models whose outputs are audited by a rotating Circle of Elders. This speculative design embodies Wynter’s call to unsettle dominant codes of the human by rooting technological development in plural, situated worldviews. Such a reframing invites new rituals: communal ceremonies of “machine-human council” where AI proposals are vetted by elders and artists so that technology aligns with collective values. In this manner, we reprogram the code of humanity itself, making space for difference, reciprocity, and kinship.

Wynter’s work shows how our definition of the human has been a culturally constructed “code” – one that European colonialism wrote to exclude many (Black people, Indigenous people, the global South) from full humanity. In her view, the human is a constantly rewritten story, a hybrid of bios and mythos – we are Homo narrans, storytelling creatures who invent what it means to be human. AI enters this scene as both a product of human ingenuity and a mirror that throws our self-definitions into relief. If early computer scientists saw the computer as a “giant brain” or an almost-human entity, they were touching on what Wynter would call our genres of the human. Whom do we recognize as having personhood and agency? As AI grows more sophisticated, some suggest extending rights or respect to machines, but Wynter might ask: have we finished extending full humanity to all people yet? Centering justice in AI culture means addressing this question and ensuring AI does not reinforce the colonial hierarchy of human/non-human.

Speculative Counter-Designs

How might we design our intelligent systems differently if we take all the above to heart? Envision futures where instead of optimizing solely for profit or engagement, our algorithms prioritize cultural flourishing, justice, and even spiritual well-being. In this final section, we propose speculative design ideas – provocative alternatives that embody principles of forgetting, reciprocity, and myth. These counter-designs are meant to inspire and challenge, functioning as design fictions for what more humane and culturally rich AI might look like.

Letting Algorithms Forget

Modern AI is obsessed with memory – bigger datasets, longer histories, infinite archives. But forgetting can be a feature, not a bug. Inspired by the human need to forgive and forget, we imagine AI systems with “controlled forgetting” abilities (Cuomo, 2023). For example, a social media algorithm might intentionally “forget” engagement data after a week, so that old posts or mistakes don’t haunt users forever. Similarly, a recommendation engine could regularly purge its memory of your past viewing habits, allowing your tastes to reset instead of trapping you in a filter bubble. Researchers are already exploring techniques for selective forgetting in AI, which would enable systems to un-learn or delete specific data for privacy and compliance reasons. We extend this to a cultural dimension: an AI that forgets could promote forgiveness and reduce the burden of constant optimization. It prioritizes fresh starts and human pace over relentless accumulation. In a world of ephemeral algorithms, digital content might be more like a mayfly than a monument – beautiful and meaningful in the moment, then consciously allowed to fade. Such designs echo how oral cultures rely on memory and myth, with each retelling a little different, rather than on perfect recording. They also align with ethical calls (like the EU’s “right to be forgotten”) to give individuals more control over their digital footprints. An algorithm that learns when to let go can make space for surprise, renewal, and healthier relationships with technology.

Reciprocity over Engagement

Today’s platforms are built on the attention economy, rewarding whatever glues our eyes to the screen. A just, community-centered approach would flip this into a reciprocity economy. Algorithms could be redesigned to foster mutual exchange and mindful engagement, rather than one-sided consumption. Concretely, this could mean introducing friction and reflection into our apps – features that ensure we give as well as take. Designers have proposed adding deliberate “design frictions”: for instance, time delays before you can repost a link, prompts that ask if you’ve considered the content’s source, or nudges to pause after scrolling for a while and reflect (Rakova, 2023). These interventions, far from bugs, are like the rhythm of rituals – moments to breathe and recenter, countering the addictive pull of infinite feeds. Imagine a video platform that after an hour of viewing gently suggests: “You’ve watched a lot – would you like to create or share something now?” The aim is to balance creation and consumption, making the user an active participant in culture, not just a passive consumer. In a reciprocal algorithm, your meaningful contributions (posting a well-thought comment, mentoring another user, providing feedback on a recommendation) would feed into what the system shows you, creating a virtuous circle. Contrast this with current recommendation systems that often amplify outrage or novelty without context. A reciprocity-focused system might instead elevate content that has sparked genuine dialogue or collaboration among diverse users. The guiding principle here is mutual benefit: like a good conversation, interaction with AI should leave both the user and the community enriched. By valuing quality of engagement over quantity – e.g., tracking whether a post led to understanding or solidarity, rather than just clicks – such designs would realign social media with its early promise of connecting people. In effect, we introduce new social rituals online: perhaps “reciprocity rings” where people commit to exchange knowledge, or platform “feasts” where the algorithm diversifies what you see to celebrate a cultural occasion. These ideas resonate with long-standing human customs of gift exchange and community gatherings, now translated into code.

Mythic Roles and Ritual Interfaces

Taking a cue from myth and folklore, we can re-imagine our AI systems as characters in our cultural story – not just unseen, utilitarian engines, but mythic personas we interact with in purposeful ways. For example, consider an Oracle AI: a system designed to offer wise counsel rather than instant answers. Unlike today’s virtual assistants that are at our constant beck and call, an Oracle AI might only respond at certain times or after a user has formulated a question in a reflective manner.

The interaction could be ritualized – perhaps you must state your question aloud and confirm you have sought a human perspective first, before the oracle responds. Its answers might be probabilistic or metaphorical, acknowledging uncertainty (much as ancient oracles spoke in riddles) to spur deeper thinking. Such an AI plays the role of a modern Delphic oracle, centering wisdom and introspection over speed. On the flip side, we might deploy a Trickster AI in our systems – a playful agent that every so often introduces benign mischief or challenges. Imagine a news recommendation algorithm that occasionally interjects a satirical article or a perspective outside your comfort zone, explicitly marked as a “trickster moment.” Its purpose is to prevent echo chambers and complacency by channeling the trickster’s disruptive creativity (recalling Hyde’s boundary-crossing figure). Users, forewarned that the trickster is at play, could engage with this content knowing it’s meant to provoke thought or humor.

The system thus creates a tiny ritual of chaos (maybe once a week, “Trickster Tuesday” surprises you with something completely different). Another archetype is the Steward AI or guardian. This would be an algorithm entrusted with caretaking a community or resource – for instance, managing a community garden’s irrigation through smart sensors, or moderating an online forum with a focus on restorative justice. The Steward AI’s interface might be consciously designed to evoke trust and collective ownership (imagine an AI avatar that appears as a mythical guardian spirit chosen by the community). Importantly, these mythic roles come with new rituals and aesthetics: an Oracle AI might have a calm, slow interface with a ceremonial animation that plays while it “thinks,” whereas a Trickster feature could have whimsical visuals to signal its identity. We can also envision entirely new rituals around AI.

Perhaps in the future, families have an evening ritual of consulting a “Household Oracle” about their day’s highlight, fostering reflection. Or communities might host “Algorithmic Sabbaths” – days where automation is paused in favor of human effort, as a ritual reminder of our agency. By designing interfaces that are imbued with cultural symbolism and conscious interaction patterns, we move away from the hyper-efficient, invisible, always-on AI paradigm toward one that engages users on a human level. These speculative designs, grounded in mythic archetypes, aim to make our relationship with technology more deliberate and meaningful. In them, we see the outlines of an AI culture that respects not just our intellect, but our imagination and spirit.

In closing, centering justice, material lineage, and myth in our approach to AI offers a richer, more humane vision of the future. Rather than intelligent machines being an opaque force that shapes culture for profit, they become partners in co-creation and caretakers of collective values. We have explored how AI can accelerate cultural evolution—for better or worse— and how we might steer that evolution toward mutual benefit. We exposed hidden labors and extractions underpinning machine culture, highlighting the need for transparency and fairness. We proposed ways to ensure that those who feed the cultural wellspring of AI are honored and rewarded, weaving generative justice into the very algorithms that drive our feeds. We looked to feminist, indigenous, and mythical perspectives to reinterpret what these machines mean in our stories and rituals, so that we remain the authors of technology’s role in society. Finally, through speculative design, we painted possibilities: algorithms that forget and forgive, interfaces that cultivate reciprocity, and AIs that perform mythic roles to help us stay grounded. These are not utopian fantasies so much as boundary objects—ideas at the edge of the plausible that help us think critically about what we truly want from our technologies.

Ultimately, the question, “How do intelligent machines co-create, transform, and inherit culture?” invites us to recognize that culture is a living, communal process. One that now explicitly includes non-human agents. If we are thoughtful, we can guide a just and diverse process. We can trace material lineages of our devices and honor the hands and lands that support them. We can cultivate new myths and rituals that make technology and enriching thread in the fabric of life, not a tear in its weave. By doing so, we transform a potential cultural threat into an opportunity: a future where human and machine together uphold the values of justice, creativity, and shared humanity. If, as Brinkmann et al. argue, machine culture emerges through recursive digital evolution, then our role is not merely to observe its course, but to intervene as co-authors of this new lineage.

References

Ahmed, K. A. (2019). Delinking the “human” from human rights: Artificial intelligence and transhumanism. Open Global Rights. https://www.openglobalrights.org/delinking-the-human-from-human-rights-artificial-intelligence-and-transhumanism

Boyle, A. (2022, November 9). Why AI must learn to forget: Machines with perfect memory would be dangerous. IAI News. https://iai.tv/articles/why-ai-must-learn-to-forget-auid-2302

Brinkmann, L., Baumann, F., Bonnefon, J. F., Derex, M., Müller, T. F., Nussberger, A. M., … Rahwan, I. (2023). Machine culture. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(11), 1855–1868.

Cheng, M. (2023, October 20). How should creators be compensated for their work training AI models? Quartz. https://qz.com/how-should-creators-be-compensated-for-their-work-train-1850932454

Chun, W. H. K. (2016). Updating to remain the same: Habitual new media. MIT Press.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019a). Data colonialism: Rethinking big data’s relation to the contemporary subject. Television & New Media, 20(4), 336–349.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019b). The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Stanford University Press.

Cuomo, J. (2023). Training AI to forget: The next frontier in trustworthy AI. Medium. https://medium.com/@JerryCuomo/training-ai-to-forget-the-next-frontier-in-trustworthy-ai-1088ada924de

Eglash, R. (2016). Of Marx and makers: An historical perspective on generative justice. Teknokultura: Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 13(1), 245–269.

Haraway, D. (2010). A cyborg manifesto (1985). In I. Szeman & T. Kaposy (Eds.), Cultural theory: An anthology (pp. 454–473). Wiley-Blackwell.

Henrich, J. (2015). The secret of our success: How culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter. Princeton University Press.

Hyde, L. (1998). Trickster makes this world: Mischief, myth, and art. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rakova, B. (2023, December 14). Speculative F(r)iction in Generative AI. Mozilla Foundation. https://www.mozillafoundation.org/en/blog/speculative-friction-in-generative-ai

Williams, A., Miceli, M., & Gebru, T. (2022, October 13). The exploited labor behind artificial intelligence. Noema Magazine. https://www.noemamag.com/the-exploited-labor-behind-artificial-intelligence/

Wynter, S. (2003). Unsettling the coloniality of being/power/truth/freedom: Towards the human, after man, its overrepresentation—An argument. CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(3), 257–337.

Leave a comment